News

HOS Blog: Who is “Diverse”?

Who feels included when we use the word “diversity”? Whom are we talking about? Dr. Derrick Gay posed these questions to our students during our all-school meeting this week. Dr. Gay is one of the leading strategists and thinkers around diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging (DEIB) work in independent schools around the world, and his work extends deeply into the corporate and non-profit sectors as well, from Barilla to Sesame Street.

In response to his question, students offered that when we typically think and talk about “diversity” or a “diverse person,” we are referring to people of color, members of the LGBTQ community, people from a lower socioeconomic status, religious minority groups, or other often-marginalized populations. That framing appropriately recognizes the ongoing challenges of individual bias and systemic impediments to equity in our society. But it also – students shared – sometimes has the effect of pushing away or discouraging engagement from people who don’t see themselves reflected in that definition of “diversity.”

Dr. Gay offers, instead, a common-language understanding of the word. Any one individual cannot be diverse, as the term only makes sense when referring to a group. And given the reality that we all come with complex identities and perspectives, we all contribute to the diversity of the communities we find ourselves in. I have known and worked with Dr. Gay for many years, and one of the things I appreciate most about his approach to this critical, difficult, and sometimes polarizing work is his insistence that DEIB includes everybody; it is the only way it can be successful. The work starts with each of us – understanding our own identities and the influences that have shaped our worldview, for good and for ill. From that common starting point, we can each find ways to celebrate the diversity of our communities and work together to do the hard but indispensable work of making our communities more inclusive and equitable. That framing informs our approach here at BUA, aligns with the mission and character of this community, and is, I believe, one of the keys to doing this work in an impactful, sustainable way.

Student Council President Lizzie Seward Delivers Opening of Term Remarks

On Tuesday, September 6, 2022, BUA Student Council President Lizzie Seward '23 delivered welcome remarks at our opening all-school meeting.

Good morning everyone! I hope you are all as excited as I am to be here at 8:30 in the morning! As the sun sets on our summer, I would like to welcome everyone back to BUA, and to welcome the new students into our community. Mr. Kolovos asked me last week to speak here today, and he told me to offer my very sage advice as we enter a new school year. I don’t know how helpful I can be with that, but I will tell you all a few things I’ve learned since I started high school here.

First and foremost, I know it is incredibly tempting, but I want you all to know that candy from the GSU convenience store does not count as a lunch, and should not be considered one. I understand that it’s quick and easy when studying for finals, but I promise you will perform considerably better with nutritious food. And even if you can find a protein bar with enough protein to help with your gains, they really are just snacks. Unfortunately, I learned that the hard way, and refuse to make any further comments on that.

Second, and this is perhaps another lesson I have learned the hard way, is understanding when you need to seek out help. Whether it’s academic or emotional, you’ll find that stress will pile up quickly while you’re here. When you’re dealing with challenging courses, extracurriculars, eventual college stress, and personal issues, it’s easy to let it build up without noticing. But you can find comfort in knowing that there is a support system here for you.

Last year, not even a full month into the school year, I had already taken so much on and I crashed hard. I was running a club, I was taking my first BU course, we were coming out of the strange COVID year, and I was dealing with a lot of things in my personal life. For the first time ever (I’m not kidding), I took a quiz I thought I was prepared for, and I failed it. Literally 27% out of 100 failed it. Worst of all, it was in my first BU class, and I felt like I needed to prove myself as the only high schooler against the older university students. I remember showing up 20 minutes late to Latin because I had been crying to Dr. Proll, and later that day I spent another hour or so crying to Dr. A. in the Black Box. I know it’s barely been a year since that happened, but I look back somewhat fondly now on how willing my teachers were to listen to me. Dr. A. even gave me an entire roll of paper towels to wipe my tears with.

You might be judging me for embarrassing myself so easily in front of teachers, but someone told me once that it is admirable to be so willing to express your emotions. It may seem awkward to ask for help, but your teachers and classmates are all here for you, and they want to see you succeed. I know we are all surrounded by such brilliant people, and it’s easy to feel inferior. But you are here for a reason, and you are in a community that ultimately wants you to learn a lot and optimize your high school experience. It really does help to talk to someone about what you’re going through, and at BUA, people are willing to help.

Third and finally, make the most of the time you have here before it’s too late. This is mostly for my fellow seniors, and I am unfortunately still learning this lesson myself.

I’ve spent a lot of time assessing my personal values recently, and I’ve decided that my biggest fear in life is to live with regrets about the past. Although that seems impossible to achieve, will I not live contentedly knowing that I have done all that I can to foster our sense of community? Ideally I will leave high school with memories that I can cherish. I don’t want to enter this final year of school worrying about what other people think, or what colleges I have to choose and apply to. We only really have four years here, but isn’t it interesting to see how far we’ve all come? Haven’t we all matured and grown up in our own ways without even noticing it? And yet, I still feel as though we barely know each other as a class. We haven’t even seen each other’s faces in three years. I know we are about to enter the most challenging time of our high school career this semester, but I implore you; go to Fall Fest, stay up all night at Lock-In, dress up and go to Semi, play video games in the JSR, maybe even forego a Mugar study session to get your work done in the QSR. The heart of our community lies within the BUA building, and we ought to spend more time there.

We have spent too much time worrying about our futures, which seemed so grim two years ago, that we never spent time dwelling in the present moment. When we leave at the end of the year, we’ll all inevitably part ways and scatter across the world. We’ve already seen it happen with previous classes, and while it’s exciting, would we not rather enter the next chapter of our lives with no regrets about this current chapter we’re in? We will always be on this earth, so what’s the point of worrying now about where we will go to college or what’s ahead in our lives? Let us enjoy the time we have left together and strengthen our bonds with each other so that we may forever look back on this year with fondness.

And for everyone else who still has more than a year left here, the aforementioned still applies. We shouldn’t curate an experience here that we will look back on in regret. Our community is so loving, and this year being the first where we come back with lightened COVID mandates indicates that it is a time to rebuild our bonds to each other, and build new friendships. I confess no belief in God, or any other denominational deity, but I do believe that a higher power resides in our community, and ideally we ought to foster it and nurture it so it may grow back stronger than before.

I started this speech mentioning how the sun has set on the summer, and yet a new dawn has begun to rise over our community. And while I cherish the memories I have made here in previous years, may this day mark the beginning of a beautiful new year for us all. Thank you.

On Kindness: Head of School Chris Kolovos Delivers Opening All-School Meeting Address

On Tuesday, September 6, 2022, Boston University Academy Head of School Chris Kolovos welcomed students, faculty, and staff back to school with the following opening remarks on the theme of kindness, a touchstone of the BUA school community.

On Kindness

Good morning. It is a real pleasure to see you all today. This is a year we have all been looking forward to for quite some time. It is a year that promises a level of normalcy that we have not experienced in quite a while – and that you all deserve. In just a few days, we will lean back into our traditions, with a group of us heading off to Camp Burgess for the first time since before the pandemic.

It is also a special year for another reason. This marks the 30th anniversary of this school's existence. It is a chance for us to think back on the legacy we have inherited from the teachers, staff, and students who have come before us and a chance to dream about the future that we will build together.

In a few moments, I will welcome Lizzie Seward, our Student Council president, up to offer a few words of welcome. But before we do that, I'd like to offer some thoughts as we start the term together, as I do at the start of each of our terms.

My talk this morning is prompted in part by my son, Charlie, whom many of you have heard about; if you have not, you will hear plenty over the next few years! He is two years old. Every morning, this is his routine. He comes downstairs and, before demanding his milk, he insists on seeing his toaster. Now, mind you, this is not an actual kitchen appliance. It is a toy toaster we bought from a Greek online toy store. If you press a button, it announces what kind of toast it's making – how dark or how light the toast should be; whether there's peanut butter or marmalade or honey on the toast. I'm not sure why he loves this toy; it's a really strange little thing. But he loves it. Before he starts his day, he has to go to “Toaster” and ask him if he had a good sleep. “Toaster, have you had a good sleep?” My wife and I smile every morning when we hear that. As I think about it, the reason is because it gives us hope that we are raising a kind person.

This morning I want to talk about kindness. It is a word that we use a great deal around here, and for good reason. We talk about a kind and curious community made up of kind and curious people. I am justifiably proud that those things are true, especially because they are deeply countercultural in a world that is focused so much on achievement, getting ahead, and, increasingly, incivility. But it is a touchstone for us here at BUA. And I think it's worth exploring together. So I'll offer just three ideas this morning about kindness.

Kindness is an Action

Take a moment to think about a time when somebody was kind to you. Think about where you were; think about what they did; think about how it made you feel. Some of you might notice a little warmth in your chest. You might be cracking a half smile.

Kindness is not just sympathy or empathy, although those things may well be required for true kindness. Nor is it being nice. There is a superficiality about being nice. Kindness is different. Kindness is action. It is a choice we make. It is a choice we make to do something that inspires a positive feeling in another human being – often with no benefit to ourselves, sometimes with a cost to ourselves.

At times, being kind is easy. It is easy in those moments when we are relaxed, or when we are interacting with somebody who is close to us or somebody we love. At other times, though, it is harder. I think about a day, like today, which promises to be pouring. I imagine some of you being late to your BU class and still making the decision to hold the door outside the GSU for somebody you do not know, with nobody around you to witness it and give you credit. You choose to hold the door anyway. Those small moments become habit. It is in those small moments when character is built. Those are the things we expect from you when we talk about being kind.

Kindness Feels Good

Earlier this summer, I was at Trader Joe's. I was in a rush. I was a little nervous because of COVID: it was crowded, and I have a young family. I was wearing my mask, it was hot, and I was impatient. As I turned the corner from the produce section to the refrigerator section, I saw an old woman reaching up for a package of sliced cheese near the top of the refrigerator section. I felt disgusted by the people standing around her not helping. I paused there feeling self-righteous and angry, and then intensely stupid for not doing the thing I should have done from the beginning, which is to go over and help her. That’s what I did. As I began to walk away, she turned to me, took my arm, and asked, “Can you do something for me?” I said, “Sure.” She said, “Please tell your mother that she raised you well.” I still have not told my mother – I should. But I will tell you this: I had a much better day after that moment with the old woman at Trader Joe's.

There is something physiological – something chemical – about kindness and its effect on us. Some of you might have studied this in your classes. Being kind has been shown to produce elevated levels of oxytocin, dopamine, and serotonin. It can decrease blood pressure. It leads to something that is more colloquially called a “helper's high.” We have evolved this way, researchers think, in cooperative and altruistic communities.

But there are more than just short term benefits that come from kindness. Those of you here last year may remember me talking about my old headmaster, Mr. Jarvis, who was a man of the cloth. I was reading one of his talks recently, and he included this passage: “I have been present at a number of deaths. I’ve never yet heard a dying man or woman brag about how much money he made or how successful he was. My experience is that a dying man looking back on his life is proudest to have helped people, of having used his time and talents to do something for others.” To do something for others. Kindness produces not just an immediate benefit, but also long term fulfillment and purpose.

Kindness is Contagious

Many of you know that I love and admire Mr. Rogers, who was a longtime host of a children's program on PBS. One Sunday evening, my wife and I watched “A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood” starring Tom Hanks about the life and times of Mr. Rogers – a man who is the closest thing to a saint we have seen on television. I came to work the next morning in a much better mood, much more patient, and a much better listener. I simply wanted to be a better person because of the model that he set.

There is real science too – dozens of studies from social psychology – supporting the idea of a contagion effect of kindness. The studies show that when people observe others being more generous, more loving, and more kind, the observers adopt similar behaviors. Those actions create ripples in a community. Think about the line of cars at a drive through when somebody pays for the car immediately behind them, and then that process continues sometimes for minutes, sometimes for hours. It is that kind of ripple that I see in this community – in all of you.

*****

You have heard me recite this adage before, but it bears repeating: “From those to whom much is given, much is expected.” You all have been given so much, not the least of which is the education that you have received and you will receive here. We appropriately expect a great deal from you. I ask you to find a way today, this week, this year to do something that is within all of our means: be kind to another human being. Maybe that means helping a new student find her way when she's looking for the black box theater. Maybe it's holding the door. Maybe it's reaching out to somebody at lunch who looks like they could use a friend. Find a way to make somebody else's day better and create those ripples throughout our community. Thank you very much, and have a wonderful school year.

HOS Blog: Community around a Campfire

I’m writing to you from Camp Burgess, where our 9th and 10th graders have enjoyed several days of ropes courses, rock climbing, kayaking, swimming, cards, board games, and bonding. This year promises a return to normalcy we have not experienced since the start of the pandemic, including the revival of traditions like this one. It is heartwarming to see the smiles on our students’ faces, to hear them laugh, and to watch the spark of lifelong friendships.

On our first night here, students gathered in an outdoor amphitheater for a bonfire and s’mores. Mr. Stone called for an impromptu talent show, inviting students – individually or in groups – to volunteer to come down to the stage/fire pit areas and share a talent before getting their s’mores. What started as a crowd control measure to make sure we didn’t have dozens of teenagers roasting marshmallows at the same time turned into something really special. Students sang everything from Don Maclean’s American Pie to classical Chinese opera; Taylor Swift to Heads, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes. We heard knock-knock jokes, saw back flips, witnessed a revival of the Macarena, enjoyed original rap songs, and much more. What struck me most is how these kids supported one another. The applause was riotous, no matter the performance. They encouraged one another to get up there. They created a space where everybody felt comfortable acting silly, being vulnerable, and sharing a piece of themselves. That is remarkable in any setting, let alone one where half of the students are new to the community. I feel very lucky to be part of a place that fosters that kind of belonging; that’s rare in the broader world, but it’s the expectation here. AndI’m proud of that. We are off to a very good start.

Curricular Innovation in English, History

As a result of the vision and hard work of the faculty this spring and summer, and inspired by conversations with students over the years, BUA students will engage in a revised history and English curriculum this year.

BUA’s humanities program has been, since the school’s founding, one of its great strengths. Our mission highlights the promise that, at BUA, students will “read deeply” and “think critically.” Those ideas permeate the English and history classrooms. History students dive into primary sources, eschewing schools’ traditional reliance on textbooks and challenging students to engage with language and ideas that push their intellectual ability. In English, students likewise read challenging, rigorous texts that one would expect to see on a college syllabus. In both departments, students test their ideas with one another in conversation around a seminar table, often staying after the bell or carrying those discussions into the hallway. Our graduates often tell us that they learned to write at BUA, a skill that only comes with practice and mentorship, which our inspired and inspiring teachers have provided for decades. All of those features will continue.

We are also proud of BUA’s traditional focus on the Western humanistic tradition, where students have the opportunity to ask some of the most basic questions of human existence in conversation with the Western literary canon and giants of Western philosophy: Why am I here? What is my role in society? What does it mean to live a good life? These are questions that our students are naturally asking. The curriculum has provided a vehicle for that exploration and will continue to do so.

But there are limitations to this approach. It can give the misimpression that the Western tradition is the only or a superior source of wisdom. It may not provide opportunities for our increasingly diverse student body to see themselves reflected in the literature and history they study. And it may sacrifice knowledge that is essential to our students as they prepare to be citizens and leaders in a global world. We have heard those concerns from our teachers, students, and graduates – all of whom value our traditional approach and see the need to address the limitations.

The path our teachers have chosen going forward preserves the richness of our traditions while injecting a global and diverse outlook. Courses are organized around themes, many of which traverse disciplines and all of which have deep relevance for our students’ lives in the 21st century. The course descriptions linked above provide more context, but to give you a sense:

- In 9th-grade English, Self and Society: The Literary Canon in Conversation, students will still read mainstays of the literary canon, but also put those texts in conversation with rigorous, rich texts outside that tradition. They will read Homer’s Odyssey, for example, alongside Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon; Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice alongside Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West – exploring common themes around identity, the boundaries between self and community, and our understanding of heroism and virtue.

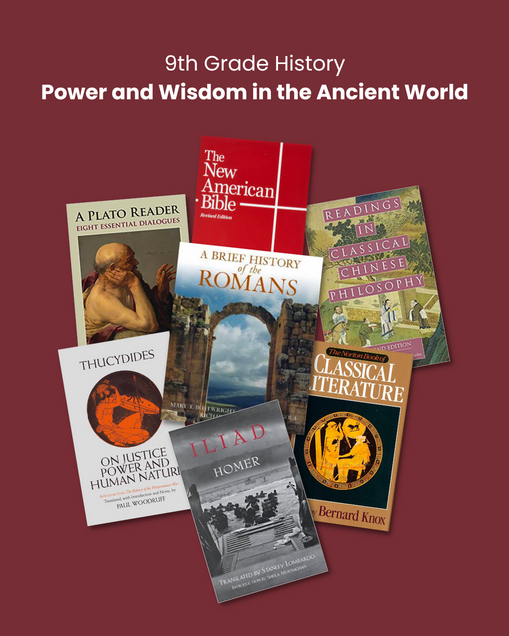

- In 9th-grade history, Power and Wisdom in the Ancient World, students will continue their exploration of Greece and Rome but add a deep dive into Chinese dynastic history and philosophy. In the process they will investigate ideas of good government and the meaning of a good life.

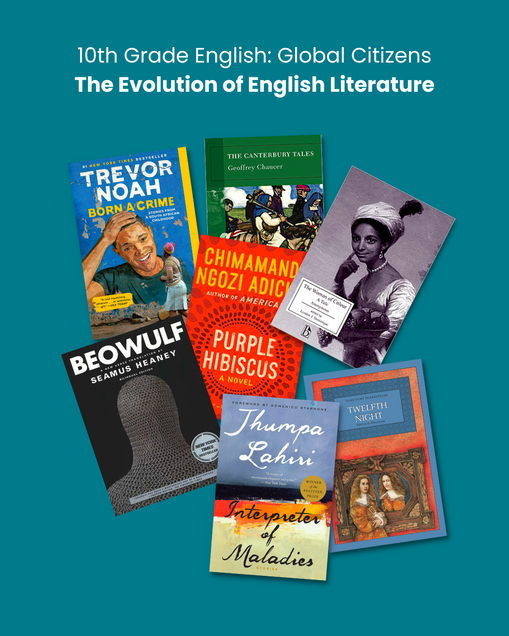

- In 10th-grade English, Global Citizens: The Evolution of English Literature, students will continue to engage with some of the great canonical works of British literature – Beowulf, The Canterbury Tales – while broadening the aperture to include post-colonial literature from the English-speaking world, like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Purple Hibiscus and Jhumpa Lahiri’s Interpreter of Maladies. Thematically, they will trace the evolution of literature in the English-speaking world and use that as a lens to explore what it means to live in an increasingly global world.

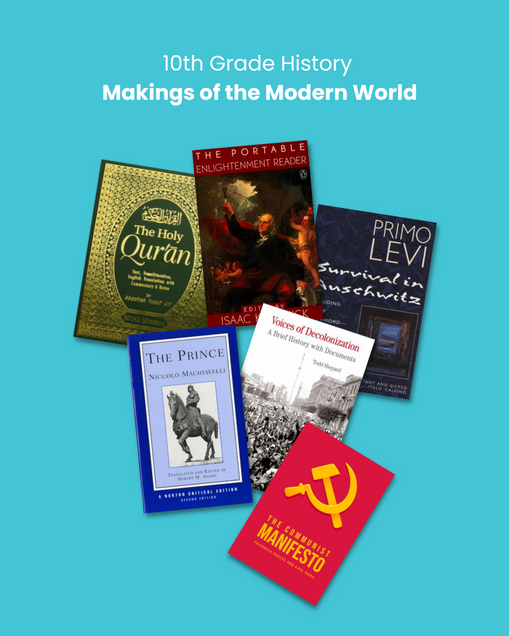

- In 10th-grade history, Makings of the Modern World, students will continue to read the great philosophical works of the European Enlightenment but will pair that with a similarly rigorous investigation of topics we believe they will need as global citizens: the Islamic world; pre- and post-colonial African history; and the 20th-century world, including a focus on the Holocaust. In so doing, they will address abiding questions: the relationship of faith to the public sphere; the development of the concepts of human rights; and the moral obligation of a citizen to the community.

Please refer to the course descriptions to explore these courses and similar shifts in the 11th and 12th grade.

Dr. Monica Alvarez Steps Into Director of Equity and Inclusion Role

We are excited to announce that, starting this fall, BUA English teacher Dr. Monica Alvarez will step into the newly-created Director of Equity and Inclusion role at our school.

Dr. Alvarez came to BUA following fourteen years at Trinity School in New York City, where she taught English and helped lead that school’s DEI efforts as Equity & Inclusion Coordinator. Since arriving at BUA in the fall of 2021, Dr. Alvarez has been an inspiring teacher for 9th and 10th graders, a trusted advisor, club leader, and co-chair of the student-faculty Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee. She will continue to teach ninth and tenth-grade English alongside this important leadership role.

Dr. Alvarez offered the following reflection about her new responsibilities:

“Two of my favorite things at BUA are the deep mutual appreciation and genuine care that shape so many of the interactions among its members. This year, I am looking forward to discovering the ways in which BUA can nurture this appreciation and care into a sense of belonging: of joyfully co-creating a learning space that spills beyond the walls of the classrooms and encourages its members to fully show up, knowing we inhabit a space where we are seen for all that we are. What an exciting time lies ahead!”

As BUA’s inaugural Director of Equity and Inclusion, Dr. Alvarez will work across constituencies – students, faculty, staff, parents, alumni – and lead the school’s efforts to fully live up to our core values of community and inclusion. The work will touch on many areas of school life: student support, parent engagement, admissions, professional development, curriculum, pedagogy, hiring, and others.

In creating the position, Head of School Chris Kolovos noted:

“I am proud of our school’s commitment and progress around diversity and inclusion. The rich diversity of our student body is one of the key reasons for our excellence. We stand out among our peer schools for being a place where all kinds of young people can feel at home and part of the BUA family. We have taken great strides in making BUA more accessible and our policies more fair. But the work is never done. I am so grateful to Dr. Alvarez for taking on this role at this pivotal moment. She loves and understands BUA, having gained an appreciation for what makes us special. She also has a deep respect for community voice and instinct for building consensus. She is in an ideal position to help us nourish our traditional strengths, identify areas for improvement, and move forward together.”

He went on to stress, “DEI is not one person’s job. It is the work of the entire community and only succeeds when we are all involved. I know the BUA family will embrace Dr. Alvarez in this new role, and I look forward to partnering with her for years to come.”

BUA Announces Curricular Innovation in English, History

In an August 5 letter to current students and families, Head of School Chris Kolovos announced exciting news about curricular innovation in the school's English and history programs. Read the full text of his communication below.

Updated Booklist

In June, we shared both the summer reading list and the term-time booklist for classics, math, and science. The reason for not including the booklist for English and history at that time was because our teachers in those areas have been deeply engaged, for several months, in a project to revise the curriculum, focused largely on the 9th and 10th grades, but also including changes in the junior and senior years. With that work completed, the updated booklist for the 2022-2023 academic year is available at this link.

English & History Curricular Innovation

As a result of the vision and hard work of our faculty this spring and summer, and inspired by conversations with our students over the years, our students will engage in a revised history and English curriculum this year. I invite you to read the course descriptions at the links above.

BUA’s humanities program has been, since the school’s founding, one of our great strengths. Our mission highlights the promise that, at BUA, students will “read deeply” and “think critically.” Those ideas permeate the English and history classrooms. History students dive into primary sources, eschewing schools’ traditional reliance on textbooks and challenging students to engage with language and ideas that push their intellectual ability. In English, students likewise read challenging, rigorous texts that one would expect to see on a college syllabus. In both departments, students test their ideas with one another in conversation around a seminar table, often staying after the bell or carrying those discussions into the hallway. Our graduates often tell us that they learned to write at BUA, a skill that only comes with practice and mentorship, which our inspired and inspiring teachers have provided for decades. All of those features will continue.

We are also proud of BUA’s traditional focus on the Western humanistic tradition, where students have the opportunity to ask some of the most basic questions of human existence in conversation with the Western literary canon and giants of Western philosophy: Why am I here? What is my role in society? What does it mean to live a good life? These are questions that our students are naturally asking. The curriculum has provided a vehicle for that exploration and will continue to do so.

But there are limitations to this approach. It can give the misimpression that the Western tradition is the only or a superior source of wisdom. It may not provide opportunities for our increasingly diverse student body to see themselves reflected in the literature and history they study. And it may sacrifice knowledge that is essential to our students as they prepare to be citizens and leaders in a global world. We have heard those concerns from our teachers, students, and graduates – all of whom value our traditional approach and see the need to address the limitations.

The path our teachers have chosen going forward preserves the richness of our traditions while injecting a global and diverse outlook. Courses are organized around themes, many of which traverse disciplines and all of which have deep relevance for our students’ lives in the 21st century. The course descriptions linked above provide more context, but to give you a sense:

- In 9th-grade English, Self and Society: The Literary Canon in Conversation, students will still read mainstays of the literary canon, but also put those texts in conversation with rigorous, rich texts outside that tradition. They will read Homer’s Odyssey, for example, alongside Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon; Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice alongside Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West – exploring common themes around identity, the boundaries between self and community, and our understanding of heroism and virtue.

- In 9th-grade history, Power and Wisdom in the Ancient World, students will continue their exploration of Greece and Rome but add a deep dive into Chinese dynastic history and philosophy. In the process they will investigate ideas of good government and the meaning of a good life.

- In 10th-grade English, Global Citizens: The Evolution of English Literature, students will continue to engage with some of the great canonical works of British literature – Beowulf, The Canterbury Tales – while broadening the aperture to include post-colonial literature from the English-speaking world, like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Purple Hibiscus and Jhumpa Lahiri’s Interpreter of Maladies. Thematically, they will trace the evolution of literature in the English-speaking world and use that as a lens to explore what it means to live in an increasingly global world.

- In 10th-grade history, Makings of the Modern World, students will continue to read the great philosophical works of the European Enlightenment but will pair that with a similarly rigorous investigation of topics we believe they will need as global citizens: the Islamic world; pre- and post-colonial African history; and the 20th-century world, including a focus on the Holocaust. In so doing, they will address abiding questions: the relationship of faith to the public sphere; the development of the concepts of human rights; and the moral obligation of a citizen to the community.

Please refer to the course descriptions to explore these courses and similar shifts in the 11th and 12th grade.

The work is ongoing; any curricular reform must be. But I am confident that these changes represent an important step forward that, at the same time, maintains those things that have made our approach so powerful over the years. I am deeply grateful for all the students and graduates who have shared their thoughts and helped inspire this change. And I am most grateful to our teachers, who have spent their summers working to offer our students this exciting curriculum.

A New Sun Rises Over BUA as Mural by Sitarah Lakhani ’22 is Completed

This summer, a blazing, orange ombre sun rose over BUA—the BUA back lot, that is.

This summer, a blazing, orange ombre sun rose over BUA—the BUA back lot, that is.

Over the past six weeks, a vibrant, celebratory, and inclusive mural was painted on the 4,000-square-foot exterior wall of Sargent Gym, adjacent to the Bridge Lot and visible from the BU Bridge, Storrow Drive, the Massachusetts Turnpike, and from many points along Commonwealth Ave.

The mural is the brainchild and passion project of recent Boston University Academy graduate Sitarah Lakhani '22, who conceived of this project as a sophomore at BUA. After years of persistence and hard work, her vision has finally come to fruition.

Many hands made light work of the installation, as current students, alumni, and teachers pitched in to help paint: scaling scaffolding, braving the aerial scissor lift, and bearing the searing July heat to add their brushstrokes to this massive undertaking.

Born and raised in Cambridge, MA, Sitarah has had a love for art from a young age. In 2020, she started an Instagram account, @sitarahsketches, to showcase her drawings and bring joy to others. During her high school years at BUA, under the expert guidance of master visual arts teacher Liz Cellucci, and later of Lisa Townley, Sitarah experimented in a variety of mediums: paint, pencil, charcoal, photography, and digital art. In her senior year she won the Scholastic Art and Writing Awards Regional Gold Key in the digital art category for her piece, “She’s Golden,” a self portrait. Sitarah will matriculate at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) this fall.

The mural was created and installed by Sitarah, with mentorship from muralist Amanda Hill and support from Boston University Academy and the BU Arts Initiative. Funding for the project was secured by Sitarah through private donations.

Her vision? Transforming a 4,000-square-foot blank wall into a vibrant, uplifting, and celebratory piece of public art. Sitarah writes:

“I wanted to make the space beautiful. My bright and lively design showcases the women of the BU community with a special nod to those in the fields of STEM while incorporating elements of nature found nearby. The waves in the mural represent the Charles River Campus, and are mathematically generated and perfectly in scale with the wall. The use of color that pops and the energy of BU women on campus were just some of the things that made their way into my definition of what was uplifting. It is really there though for people to take in the image on their own terms, at different moments in time. The wall, which was formerly looming over a dark parking lot, has now been transformed into a warm, joyful, and welcoming area that aptly illustrates our diverse and inclusive community.”

The mural was completed in late July. A ribbon-cutting ceremony to inaugurate the mural will be held in the BUA back lot on Tuesday, August 30. Read on for a Q&A with muralist Sitarah Lakhani '22!

Q&A with Sitarah Lakhani '22

What inspired you to create this artwork?

My inspiration for this artwork came from the wall itself. I was walking across the BU Bridge one morning the summer before sophomore year, and usually when I walk to school I always take a picture of the river. This day I happened to forget until I was walking past the wall of the Boston University Sargent Gym connected to BUA. When I first noticed the wall I was struck by how drab it looked and once I stopped to fully take it in, how large it actually was. I couldn’t believe in all my years of passing this exact spot thatI did not even realize its existence. The next thing that came to mind was how amazing the area would look with a splash of color. So many people pass the same exact spot that I pass every morning, so how amazing would it be to make each of their mornings or evenings just a shade brighter? The inspiration behind my art came from bringing others joy. I thought so many people will pass by this mural everyday and if I can make even one person smile or have a slightly better day it is all worth it.

Does the mural have a title?

The mural will have the official title of “Untitled 1.” Although I was initially considering naming the mural, as I completed it I felt it was better left to the viewer’s imagination. I feel if I had named the mural based on the waves or the figures, that is what it would be seen as. Instead, I want your eyes to be drawn wherever feels natural.

Are the figures in the mural inspired by real people?

Not really! They are inspired by my imagination and I wanted there to be as much representation as possible. I took elements of features I have seen and thought would make for an interesting composition like the slit eyebrow, a hat, or the multicolored hair.

Tell us about your choice to leave the figures’ faces blank.

My distinct art style started in 2020 on my @sitarahsketches instagram and from there, I kept going with it. The figures and people in all of my older drawings have no facial features except for eyebrows and facial hair. I think this happened due to a few different reasons but to be honest, the main reason was that I was not so great at drawing facial features, it's super difficult! My account was based on drawing the likeness of people through their forms of expression and other individual personal choices like accessories, clothing, and hairstyles. I think tying it back to the mural sketch, I am glad that I chose to stick with this style and not have defined facial features. This gives the viewer an opportunity to see themselves or even someone they might know.

What was the hardest part of the process of bringing this mural to life?

There were so many moving parts! One of the hardest parts was keeping track of everything that was going on throughout the past three years. From designing the actual image, to drafting a proposal, pulling a team together and fundraising, there was a ton going on. Also, another difficult part of this project was keeping my motivation up. There were definitely moments when I felt like I wanted to stop or quit or maybe something was moving at a different pace than anticipated or I needed to figure out how to turn someone’s ‘no’ into a ‘yes’ – but I just had to keep going. However, I was driven by my end goal and I found inspiration, motivation, and joy in the process even when it felt difficult. I had a vision that I wanted to see come to life and in the end I did it.

Were there any unexpected hurdles in the actual installation of the artwork?

I think one of the main hurdles faced in the actual installation was the weather. It was brutally hot these past few weeks but the team adapted and started working in the early morning to beat the sun that was fully shining on the wall by noon. Also, I think small things like having cars park right next to the lift or not having enough of one specific paint color were some of the smaller road bumps we ran into.

What was your mentorship with muralist Amanda Hill like?

My mentorship with Amanda Hill was everything that I could have ever imagined and more. Amanda is not only an amazing artist but she is an incredible teacher. She walked me through every single little step of the mural and taught me along the way. From learning how to create a doodle grid, to mixing the perfect skin tone, and even driving a 40-foot lift, Amanda taught me all the skills I needed to know in order to install a giant mural. In addition, Amanda taught so many other volunteers throughout the process ranging from BUA students and teachers to parents and neighbors. I truly enjoyed working and learning with her and she is definitely an inspiration to beginner artists like myself. I cannot wait to see what she does in the future!

Any advice you’d like to share with current and future BUA artists?

My advice for current and future BUA artists, and students in general, is that if you have an idea or a vision, go for it. You will never know if it is possible until you try. Sure, you might face some bumps along the way but go along with it and see your ideas through. And if it doesn’t work the first time, try again!

Summer Research Highlight: Genomic and Computational Approaches to Gene Regulation with Dr. John Quackenbush P’24

Each cell in our body contains a set of instructions, encoded in a molecule called DNA, that helps determine both our traits—including things like height, weight, hair color—and our individual risk of developing diseases such as diabetes or cancer. DNA is a long-chain polymer, and these instructions are encoded in the DNA “sequence” (the series of polymer subunits) and grouped in “genes,” each of which carries the instructions for creating one of the proteins that make up our cells.

Each cell in our body contains a set of instructions, encoded in a molecule called DNA, that helps determine both our traits—including things like height, weight, hair color—and our individual risk of developing diseases such as diabetes or cancer. DNA is a long-chain polymer, and these instructions are encoded in the DNA “sequence” (the series of polymer subunits) and grouped in “genes,” each of which carries the instructions for creating one of the proteins that make up our cells.

The sequencing of the human genome at the start of the twenty-first century gave us a catalog of human genes and provided us with tools to explore how differences in our DNA make us unique. More than twenty years later, we are still exploring how genes, and the genetic instructions that control them, ultimately determine these traits.

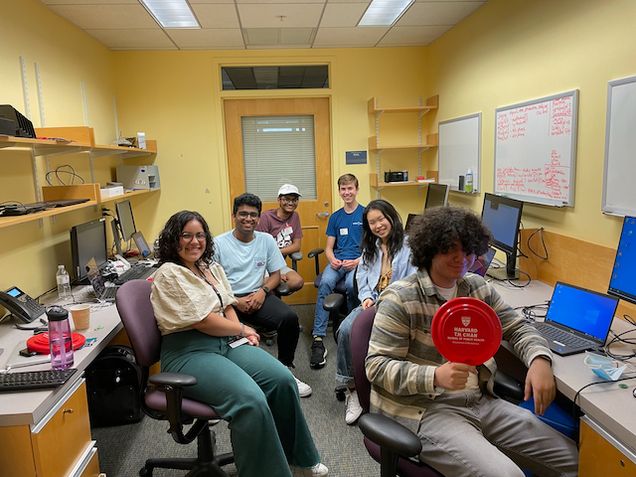

BUA parent Dr. John Quackenbush P'24, Professor of Computational Biology and Bioinformatics and Chair of the Department of Biostatistics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, is one of the world’s leading researchers in studying the links between genes and traits. His research team has developed methods that model how genes work together in networks that alter cells as they grow and develop or as they move from health to disease. This summer, seven students—four rising BUA seniors working on their senior thesis projects; one recent BUA graduate who did her senior thesis work in the lab in the summer of 2021; one rising BUA junior; and a junior from the nearby Winsor School—are working with Dr. Quackenbush and his research team to explore what one can learn about gene regulation.

BUA graduate Mia Shapoval '22, who will attend Boston University as freshman this fall, is following up on her senior thesis project in which she explored how the process of gene regulation differs between tumors in males and females suffering from lung cancer and trying to understand how changes in regulatory networks might help explain why there are sex differences in lung cancer risk, the risk posed by smoking, the rate at which lung cancer develops, and how well people respond to therapy. What drives sex differences in human health and disease is one of the most understudied problems in biomedical research and answering this question promises to provide insight into how to treat diseases using sex as a tool to select treatments most likely to be effective in each person.

Audrey Xiao ’23 and Christian Asdourian ’23 are looking at how changes in gene regulation over the course of a lifetime alter the state of our health. These “epigenetic clocks” run at different rates is different people—or even in different tissues in the same person—and contribute to many diseases. For example, decreases in lung function are normal during one’s lifetime, but the rapid decrease in function seen in emphysema appears to be a disease of dramatically accelerated aging. Audrey is looking at different ways of assessing epigenetic age, trying to understand why epigenetic age and chronological age differ between people and testing the hypothesis that lung cancer and normal tissue may show different epigenetic clocks in the same person—changes that may help shed light on how to better treat lung cancers. Christian is trying to understand whether the rate affects some genes differently than others, leading to differences in every person’s disease risk. Specifically, he is looking at how differences in lung cancer characteristics, such as tumor stage, and demographics variables such as sex or chronological age, are related to the epigenetic age of cancer tissues. If cancer is a disease involving alteration of epigenetic age, this analysis will provide insight into how and why lung tumors develop and progress in ways that are unique to each individual.

Rohan Biju ’23 is tackling the problem of how one finds interpretable patterns in gene regulatory networks that contain more than 25,000 genes and the elements that control them. Using a technique called “network graph embedding” to summarize and visualize the complex regulatory landscapes active in each cell, Rohan’s goal is to find groups of genes that are differently regulated between health and disease conditions in ways that explain what we know of the disease process. Aditya Venkatesh ’23 is exploring ways of inferring gene regulatory networks using data derived from thousands of individual cells (rather than from “bulk” tissue samples). By looking at the regulatory processes that are active the collection of individual cells, Aditya is trying to understand what cell types comprise organs and tissues—and how the composition shifts as disease develop.

Adam Quackenbush ’24 and Jaya Kolluri, a rising junior at the Winsor School, are exploring ways in which we can accelerate applications of the scientific method by finding new, completely unexpected hypotheses to test. Using large-scale datasets that measure the activity of all 25,000 human genes in each of 40 tissues in nearly 1000 individuals on whom there is extensive clinical data (including age, height, weight, sex, race, smoking status, and so on), Adam and Jaya are looking for all possible correlations and associations between different measured variables, and then using these to create an online “serendipity engine,” SEAHORSE, that allows users to ask and answer open-ended questions about individual variables or about groups of research subjects by selecting multiple demographic and other parameters. For example, one could ask “What clinical variables correlate with subject age?” Or, “What gene expression levels in which tissues are correlated with subject weight?” Or “What gene regulatory network edges are correlated with smoking status?” The hope is that SEAHORSE will allow these open-ended questions to be quickly explored and so will spur the development of new hypotheses that can ultimately be tested and validated or rejected.

Each of these students is working directly with one or more graduate students or postdoctoral fellows and participating as active members of Dr. Quackenbush’s research laboratory. They are developing and applying new methods for data analysis in the R statistical programming language, troubleshooting their software, and discussing their results and challenges with all the senior scientists in the team’s weekly group meetings. Students will be expected to present their summer’s work before returning to school and to work with their mentors on developing a scientific publication based on their work—Adam and Jaya’s project has already been selected for presentation at the 2022 Women in Statistics and Data Science conference and they have started working on a paper about their online tool.

BUA, BU Hosts NASA Downlink from International Space Station

On July 20, more than 500 middle- and high-school students and educators from across eastern Massachusetts descended on Boston University's campus for a day of space exploration and STEM education in the form of hands-on activities, lab and observatory tours, and presentations with BU faculty. Many of those in attendance were affiliated with local access and enrichment programs including Alexander Twilight Academy (a BUA partner), Upward Bound, the Calculus Project, and GROW (Greater Boston Area Research Opportunities for Young Women), among others.

On July 20, more than 500 middle- and high-school students and educators from across eastern Massachusetts descended on Boston University's campus for a day of space exploration and STEM education in the form of hands-on activities, lab and observatory tours, and presentations with BU faculty. Many of those in attendance were affiliated with local access and enrichment programs including Alexander Twilight Academy (a BUA partner), Upward Bound, the Calculus Project, and GROW (Greater Boston Area Research Opportunities for Young Women), among others.

In the BUA gym, students built rockets out of film canisters, water, and Alka-Seltzer tablets; attempted to move a balloon along a length of fishing line in a fly-by-wire design challenge; and even had the opportunity to hold pieces of the moon and Mars, courtesy of the Maine Mineral & Gem Museum. Several BUA student and teacher volunteers were on hand to assist with the activities.

The highlight of the day was the NASA In-flight Education Downlink with astronaut Bob Hines ENG '97 and Italian astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti of the European Space Agency, Crew-4 colleagues on the International Space Station. Attired in a BU Terriers jersey, Hines floated alongside Cristoforetti, whose hair stood straight up, an effect of zero gravity, as they beamed in live from the ISS to a darkened GSU Metcalf Ballroom. Answering prerecorded questions -- including several from BUA students -- astronauts Hines and Cristoforetti performed some neat tricks: slurping floating droplets of water out of midair; doing weightless flips until dizzy; and demonstrating momentum and force in microgravity.

The highlight of the day was the NASA In-flight Education Downlink with astronaut Bob Hines ENG '97 and Italian astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti of the European Space Agency, Crew-4 colleagues on the International Space Station. Attired in a BU Terriers jersey, Hines floated alongside Cristoforetti, whose hair stood straight up, an effect of zero gravity, as they beamed in live from the ISS to a darkened GSU Metcalf Ballroom. Answering prerecorded questions -- including several from BUA students -- astronauts Hines and Cristoforetti performed some neat tricks: slurping floating droplets of water out of midair; doing weightless flips until dizzy; and demonstrating momentum and force in microgravity.

After the downlink event, participants were treated to a space-themed bag lunch of moon cheese and rocket pops.

Downlink Day was organized by Sheryl Grace, associate professor of mechanical engineering in BU's College of Engineering and a former teacher of astronaut Hines. BU President Robert A. Brown; US Senator Edward Markey (D-Mass.) (Hon.’04); Calculus Project CEO and Founder Adrian Mims; and Boston University Academy Head of School Chris Kolovos, among others, delivered remarks at the event.

If you missed it, you can watch highlights of the downlink event on NASA's YouTube channel here.