News

HOS Blog: Staying Focused on DEI in the Pandemic

We will be away from school on Monday in celebration of Martin Luther King Jr. Day. This year, we will begin a new tradition: an annual MLK Day Speaker Series. I’m delighted to announce that our inaugural speaker will be Angela Onwuachi-Willig, the dean of BU School of Law. Dean Onwuachi-Willig’s fascinating research explores the intersection of race and law, and she will be addressing our students, faculty, and staff at an all-school meeting on February 8.

As challenging as things are right now, the pandemic can’t distract us from the other critical work we do in school. This school, like many others, has a mission commitment to inclusion and preparing culturally competent citizens; that is not a luxury, it’s a promise. Our 9th and 10th graders are all engaged in a weekly seminar exploring identity, stereotype, bias, and privilege. Our alums work with our students in race-based affinity spaces. Students and faculty partner in our DEI committee to grow as individuals and think about how best to move our community forward. The work is never done, but we keep at it so that we can give our students the tools they will need and so that every student and family can feel like BUA is home.

BUA Senior Named 2022 Regeneron Science Talent Search Scholar

BUA senior Zoe Xi '22 was named one of the top 300 scholars in this year’s Regeneron Science Talent Search, the nation’s oldest and most prestigious science and math competition for high school seniors.

Zoe's project, entitled "Approximation Algorithms for Dynamic Time Warping on Run-Length Encoded Strings," focuses on dynamic time warping (DTW) distance algorithms under the guidance of Bill Kuszmaul, an MIT computer science PhD candidate advised by Professor Charles Leiserson. She writes:

"DTW is a well-known similarity measure for comparing strings that encode time series data. DTW distance was first introduced by Taras Vintsyuk in 1968, who applied it to the problem of speech discrimination. In the decades since, it has become one of the most widely used similarity heuristics for comparing time series in applications such as bioinformatics, signature verification, and speech recognition.

One of the most fundamental questions concerning DTW is how to compute it efficiently. The classical algorithm for computing DTW is relatively slow (as it takes quadratic time), and it is known that, in general, no algorithm can do significantly better. This has led both practitioners and theoreticians to focus on specialized versions of the problem, for example, the case where the time series are run-length encoded. Research (such as mine) that makes algorithmic progress on these specialized versions of the problem has the potential to significantly help practitioners down the road.

My research is primarily on the theoretical front and pushes forward the state of the art for what we know how to accomplish algorithmically. It can potentially help us get unstuck on a fundamental computational problem that has many real-world applications. My primary result includes three fast algorithms that approximate with high accuracy the DTW distance between two special strings consisting of runs, where each run is a string of copies of a single letter. To my knowledge, these are the first approximation DTW algorithms with formally proven time bounds."

As a top-300 scholar, Zoe will receive $2,000, and BUA will also receive $2,000 to use toward STEM-related activities. Zoe will now be considered for a spot as one of 40 Finalists, who each receive $25,000 and participate in the final competition in March. Congratulations to Zoe on this impressive accomplishment!

HOS Blog: Schoolwork with an Audience

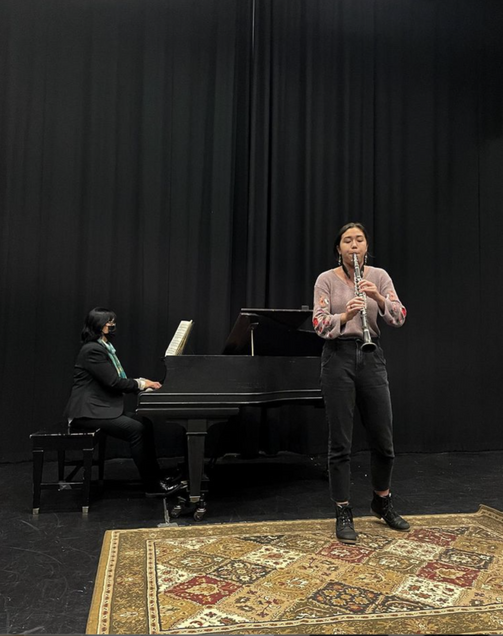

I had the pleasure of watching BUA’s annual Concerto Competition on Tuesday. Three students competed, one on saxophone, one on clarinet, and one on violin; they played challenging pieces from Villa-Lobos, Debussy, and Mozart, and did so beautifully. This language appeared at the bottom of the program: “[T]he winner will play their concerto movement with the BUA Orchestra at the Spring Concert on May 6 in the Tsai Center for the Performing Arts.” There was no grade, no course credit, no trophy — just the chance to play again on a bigger stage to a larger audience.

Later this spring, our seniors will present their theses to peers, teachers, and families on a dedicated symposium day. We have juniors working with a teacher on analytical papers for submission to the Concord Review. 10th graders recently shared their chemistry video projects over lunch with friends and teachers in the lab.

Decades of studies have confirmed that a key piece of motivation is purpose: the understanding that what we do has an impact on others. As adults, we often choose our jobs, decide on philanthropic priorities, engage in community organizations, and prioritize family because those things affect more than just us. Teenagers are no different. If we want young people to do their best work, we need to find ways to make that work purposeful, which includes creating opportunities for them to write and perform for real audiences and push the walls of the classroom out to encompass the neighborhoods, people, and societal challenges around us. I’m proud to be at a school that understands that and unleashes these remarkable students. Our future is brighter for it.

Captain Lydia Hill ’11 Gives ASM Remarks on Military Service, Mental Health

This Tuesday morning, in honor and recognition of Veterans Day, Captain Lydia M. Hill '11 addressed more than 250 BUA students and faculty at our weekly All-School Meeting in BU's Morse Auditorium. Captain Hill graduated from BUA in 2011 and went on to the United States Air Force Academy, where she received her commission in 2015 as a distinguished graduate. Pursuing a career in the Air Force, Captain Hill served as the Wing Executive Officer for the 375th Air Mobility Wing, and has deployed on assignments worldwide, including in the UK and South Korea. Currently, she is pursuing an MA in Psychology at San Diego State and will become an instructor in the Department of Behavioral Sciences and Leadership at the Air Force Academy.

This Tuesday morning, in honor and recognition of Veterans Day, Captain Lydia M. Hill '11 addressed more than 250 BUA students and faculty at our weekly All-School Meeting in BU's Morse Auditorium. Captain Hill graduated from BUA in 2011 and went on to the United States Air Force Academy, where she received her commission in 2015 as a distinguished graduate. Pursuing a career in the Air Force, Captain Hill served as the Wing Executive Officer for the 375th Air Mobility Wing, and has deployed on assignments worldwide, including in the UK and South Korea. Currently, she is pursuing an MA in Psychology at San Diego State and will become an instructor in the Department of Behavioral Sciences and Leadership at the Air Force Academy.

In her remarks, Captain Hill talked openly about mental health issues, LGBTQIA inclusion, and leading a life of service. She reflected on BUA as being “the first place I really saw people step up and be agents of change,” and shared her gratitude for a BUA teacher who inspired her "by living his life openly and with courage." Captain Hill went on to build her own legacy, founding the Spectrum Alliance for LGBTQIA airmen at the US Air Force Academy. Captain Hill's candid reflections received an enthusiastic reception from the BUA audience, with students expressing their deep appreciation in the Q&A following her talk.

We are grateful to Captain Hill for her vulnerability and candor, and for the privilege of hosting her this week.

HOS Blog: Why I Visit Classes

One of our long-time teachers recently asked me why I visit classes. My practice is to pop in for 10-15-minute observations of each teacher at least once per quarter, followed by a short sit-down for me to get more context, offer praise, and ask questions; our Associate Head of School, Dr. White, follows the same pattern. The teacher shared that he really appreciated the investment of time and the collegial conversations. But he wondered what I saw as the value of these visits when no one person can possibly offer expertise in every subject we teach. A good question.

For many years, independent school classrooms were closed-door cultures. Not here. Observing a teacher in action, talking with them about their practice, and offering specific praise means that they feel seen — something we all deserve. It gives me a chance to ask how they want to grow and align our professional learning resources to their needs. And it puts me in a position to connect teachers so that they can learn from our best resource: one another.

Having a sense of what’s happening in the classrooms also makes me a better leader. One of the reasons I so value being at a small school is for the chance to really understand the day-to-day lived experience of our students and teachers. I can’t imagine guiding the curricular and pedagogical direction of a school without that understanding.

And, selfishly, sitting in on these joyful, engaging classes is often the best part of my day!

HOS Blog: What Sports Can Do

Last Friday night, the girls’ soccer team won the league championship in a hard-fought 2-0 win. It was a cool 45 degrees on the metal bleachers, but the excitement, camaraderie, and ample pizza kept our parent and student spectators warm. The newly-formed pep squad led the cheering, and the girls on the field provided the inspiration. That experience came at a time when we most needed it, after our community suffered the tragic loss of one of our teachers last week — one that we will be feeling for a long time. As I looked around the stadium, I was struck by what sports can do for a community. Last night’s game brought us together. For ninety minutes, we cheered our student-athletes, reveled in school spirit, and just enjoyed being together. We were a family.

Sports are also one of the few places in school life where we allow students real autonomy and give them the chance to fail. Once the whistle blows, there’s precious little the coach can do. We trust student-athletes to apply the lessons they picked up in practice. And sometimes they lose. If we think of the most important lessons we’ve learned in our lives, most come from times when things did not go the way we hoped. Sports are an ideal place for those lessons and may even provide a model for what we can do in our classrooms — creating more chances for autonomy, risk taking, and, yes, failure.

Fall sports have drawn to an exciting close, so we’ll see you on the basketball court and at a fencing match.

BUA Girls Soccer Takes Home League Championship

Congratulations to the BUA Girls Soccer team, whose 2-0 victory over the International School of Boston in last night's game earned them the title of Girls Independent League champions!

Co-captain Casssandra Swartz '22 sends in this recap of the championship game:

"On November 5, the BUA Girls Soccer team departed to face off against International School of Boston (ISB) at Hormel Stadium for the Girls Independent League Championships. We played ISB for our first game of the season, and suffered a 0-2 loss. We were determined to redeem ourselves and secure the title of champions. The game began as an even battle, the ball shifting back and forth between both sides of the field. Time was running out in the half, and the score was still 0-0. Luckily, we gained an opportunity through a free kick right outside of the penalty area. Susanna Boberg '23 capitalized on this, and shot past their wall of defenders into the upper right hand area of the net, past the goalie’s arms. We were all ecstatic, and our newfound energy put us into momentum to maintain our lead and get another goal. While ISB played hard, our team played harder, doing everything we could to get another opportunity to score. This opportunity came when Alex Furman '25, with a great cross from the right corner, delivered the ball into the box where Jackson Phelps '23 connected with a beautiful header and sent the ball into the goal. With a score now of 2-0, our defense stayed strong until the very last minute to secure our victory. The whistle blew, and we all sprinted to each other in celebration, knowing that we had become the champions of the Girls Independent League, this year being only the second year that the girls soccer team has played in a league. It was an amazing night, and the best way to end such a great season.

The girls on our team have fought hard to earn our spot in the playoffs, and this was one of the best games we have played all season. Special thanks to all of our coaches -- Annie McConnon, Emma Moneuse, Gabby Glass, and Abi Ewen -- who were incredibly supportive and all guided us to victory this season. Those of us who are returning next year look forward to the next season, where we can pick up right from where we left off."

Remembering Dr. Jennifer Formichelli

Boston University Academy English teacher Dr. Jennifer Formichelli passed away in a tragic accident near her home in Mattapan on the morning of October 26. She touched so many lives in our school community, and her loss is profoundly felt.

Jennifer will be remembered as a thoughtful, highly intellectual scholar of English literature; a champion of social justice, deeply committed to equity and inclusion in and out of the classroom; a trusted advisor; a warm and loyal colleague and friend; and, most of all, an engaged and dedicated teacher who loved her students. Through her work at BU Academy, she shaped the lives of hundreds of young people. She was a cherished member of our school community and will be deeply missed.

BU Today published this moving remembrance of Jennifer Formichelli on the day of her passing. A candlelight vigil for Jennifer Formichelli will be held on Thursday, October 28 at 5:30 p.m. on Marsh Plaza.

Community members are invited to share their own remembrances or tributes to Dr. Formichelli on this webpage, or by mail at 1 University Road, Boston MA 02215.

HOS Blog: Homer with a Side of Humor

I visited a ninth-grade English class yesterday. The group was discussing an early passage in Homer’s Odyssey where Telemachus, Odysseus’s son, was expressing frustration about the bad behavior of the suitors, who were vying for his mother’s hand in his father’s long absence during his return from Troy and shamefully taking advantage of the hospitality of the household. One of the students offered, with a wry smile, “Telemachus could just do what Oedipus did and marry his mother — that would solve everything!” The teacher replied, with a wink, “And how did that work out for Oedipus?” The class had a good laugh and went right back to the task at hand.

Humor in the classroom does more than lighten the mood. It creates an emotional bond between teachers and students, and an atmosphere of emotional safety that is critical to learning. We know from decades of research that teaching and learning is fundamentally relational; students learn best when they know that their teacher knows and cares about them. A classroom where it is safe, even encouraged to make a joke, be vulnerable, and laugh together — that is a place where the door to learning is wide open.

HOS Blog: Inclusion in Five Languages

Last year, several students teamed up with our admission officers to record video information sessions for prospective students and families — not an unusual move, particularly when the pandemic made campus visits complicated. The wrinkle? They recorded those sessions in Portuguese, Spanish, Russian, and Mandarin Chinese — four languages commonly spoken in our students’ homes.

Inclusion requires action. It is necessary, but not enough to be kind, polite, and friendly. In making our admissions information sessions available in multiple languages, these students understood that, particularly for the families of our first-generation American students, we could remove a barrier and meet them where they are.

We work hard to actively create an inclusive community across the school: a holistic financial aid program that covers not just tuition but so many of the incidental expenses that pose challenges to full community engagement; affinity spaces for students and alums who identify as people of color to be together and share their experiences; a Gay-Straight Alliance serving both as an informal affinity space and one that generates ideas for community education; parent and student cultural celebrations where they can share their stories and experiences; a seminar for all 9th and 10th graders where we talk directly about about identity, bias, privilege, and action.And we have more to do. Inclusion is a core value at BUA, and I’m proud that no matter what structures we put in place, the focus shifts to what else we can do to make sure that this place feels like home for any student or parent who walks through our doors — or joins us by video.